Just outside a gas station in Seminole, Texas, a man named Peter Hildebrand stood in the heat, visibly shaken.

His eyes were red, and his voice kept breaking. He was talking about his daughter, Daisy.

“She did not die of the measles,” he said. “If there’s one thing you should know, it’s that. She was failed.”

Two children are gone, and heartbreak is spreading fast

Daisy was only eight. She was the second child to die during this measles outbreak in West Texas.

The first was a six-year-old girl named Kayley Fehr. Both were part of the local Mennonite community and hadn’t been vaccinated.

These were the first measles deaths in the U.S. in over ten years.

Distrust and fear are gripping the town

In this part of Texas, a lot of folks just don’t trust vaccines. DailyMail spoke with different people in town — moms, truckers, farmhands — and many of them said things like the shots had “dangerous stuff” in them or that Big Pharma was only in it for the money.

They really believe that.

Vaccine rates in the area are dangerously low

In Gaines County, where Seminole is located, vaccine exemptions are super high. Thirteen percent of kids in local schools have opted out of vaccines — way more than the national average of around three percent.

Last year, only 82 percent of kindergartners got their MMR shot. That’s well below the 95 percent needed for herd immunity.

Daisy’s illness started small, then got much worse

Daisy had been a healthy, lively kid. About a month before she passed, she got a fever and sore throat.

Then things got worse. She developed pneumonia. At first, her family tried home remedies like cod liver oil, which is popular in their community.

But when that didn’t work, they took her to the hospital.

She was diagnosed with strep, mono, and measles. The doctors gave her antibiotics and sent her home.

But just three days later, her condition got worse fast. They rushed her back to the hospital, but it was too late.

Her dad says it wasn’t the measles or vaccines

Mr. Hildebrand doesn’t blame measles. He blames the care she got — or the lack of it.

“The [MMR] vaccine ain’t worth a damn,” he said. “My brother’s family got it and they all still got sick — worse than my unvaccinated kids. This isn’t about the vaccine.”

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses

Measles is scary contagious. If someone has it, almost everyone around them who isn’t immune will catch it too.

The average person with measles can infect up to 18 others. That’s way more than early COVID strains, which only spread to about two people on average.

And measles doesn’t just make you sick — it weakens your immune system. In kids who haven’t had the vaccine, 1 in 5 ends up in the hospital, 1 in 20 gets pneumonia, and 1 in 1,000 can get swelling in the brain.

One to three out of every 1,000 children die from it.

The Mennonite community takes a natural approach

The Mennonite community in Seminole isn’t fully anti-vax. It’s more about personal choice for them.

Scripture doesn’t strictly ban vaccines, but a lot of people here prefer natural remedies. There are about 3,000 Mennonites in Gaines County.

Many go for things like cod liver oil to help their immune system.

At a local supplement shop called Healthy 2 U, the manager, Nancy, said, “We recommend it to everyone who gets sick.”

Opinions in town are deeply divided

Not everyone agrees, even within the same community. Outside a Walmart, two Mennonite women shared very different views.

One said she vaccinated her kids because she felt it was the right thing. The other said she didn’t — believing that illnesses like measles help build stronger immune systems.

Meanwhile, some people think the outbreak is dying down, while others say they’re hearing about more cases than ever.

Local efforts aren’t enough to stop the virus

There is a local testing and vaccine clinic in town, but it doesn’t see steady traffic. Some days it’s empty. Other days a dozen people show up.

The town health director, Zach Holbrooks, keeps reminding people that vaccines are their best shot at avoiding serious illness and death.

There are some signs around town warning people, but they’re easy to miss. You could pass through and not even know there’s a major outbreak happening here.

Measles cases are increasing across the U.S.

As of this week, more than 700 measles cases have been reported in the U.S. That’s already double the total for all of 2024.

Most of the cases are in Texas, with over 540 reported across 22 counties.

Indiana became the sixth state with an active outbreak. Others include Kansas, Ohio, Oklahoma, and New Mexico.

New Mexico reported 58 cases, mostly in Lea County. Kansas had 32 spread across eight counties.

Oklahoma had 12, and Ohio had 20 spread across four counties. Indiana confirmed 6 related cases — its first cluster.

Texas is at the heart of the outbreak

Texas is dealing with the worst of it. Around 65% of the state’s cases are from Gaines County alone.

That’s where Daisy and Kayley lived.

At least 56 people have been hospitalized, and three people have died so far — two kids in Texas and one adult in New Mexico.

The CDC has sent another team to West Texas to help contain things.

Health experts say this is what they feared. That the virus would spread from one low-vax community to another, possibly for a year or more.

Travel is helping measles reach more places

The World Health Organization says the outbreak in Mexico is linked to what’s happening in Texas.

And across the U.S., travel is a big reason measles keeps popping up. Someone brings it back from another country, then it spreads in areas with low vaccine coverage.

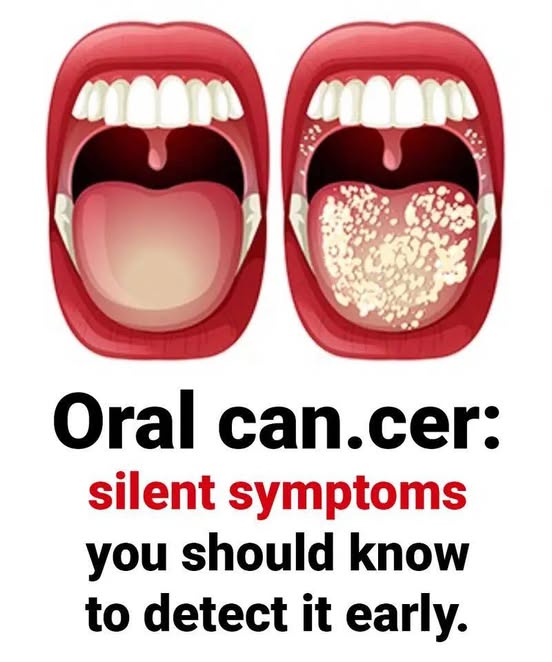

Measles symptoms can turn serious quickly

Measles usually starts with a high fever, runny nose, cough, and red eyes. Then comes the rash.

It begins on the face and spreads down the body. Fevers can shoot up past 104°F.

Most people recover, but complications can be deadly. Kids are at risk of pneumonia, swelling in the brain, and even blindness.

MMR shots remain the best defense

Doctors can’t cure measles. They just treat the symptoms and try to avoid serious complications.

The MMR shot is safe and effective. Most kids get their first dose between 12 and 15 months, and their second between ages 4 and 6.

Adults who aren’t sure if they’re protected can talk to their doctor about getting tested or just getting another dose.

The CDC says it’s fine to get an extra shot if needed.

A father grieves and calls for kindness and care

Peter Hildebrand is still trying to fight the report that says Daisy died of measles. He even met with RFK Jr. recently.

“He didn’t mention vaccines once,” Peter said. “But he was the nicest man I ever met.”

Not long after the visit, RFK Jr. posted, “The most effective way to prevent the spread of measles is the MMR vaccine.”

Now, Daisy is buried next to Kayley in a quiet Mennonite cemetery. “She was my little girl,” he said softly. “And they let her down.”